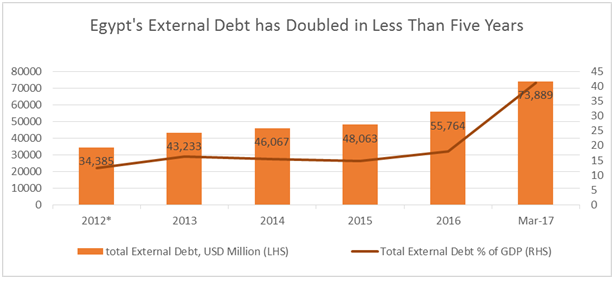

Egypt’s external debt has increased by 50 percent in just two years, according to official statistics from the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE), following several years of relatively limited debt growth and a strong position of Egypt’s external sector.

The stock of external debt stood about $74 billion at the end of March 2017, compared to $48 billion at the end of June 2015. When compared to June 2011, the figure has, in fact, doubled. While the rise in debt was necessary to shore up reserves, it is important to examine whether that move marks a mere shift in the level or a new trend.

(Graph by Dcode. Source: CBE)

To forecast potential debt scenarios, it is vital to understand what has driven the country’s recent accumulation of foreign debt.

To put it simply, if a country spends more than its income — either in capital or consumption expenditure— then it has what is called a current account deficit. In other words, a current account deficit means that the economy is not accruing sufficient savings from its income to cover investment needs. To finance this deficit, an economy needs to attract foreign capital (in the form of direct or portfolio investment), borrow from abroad or draw from its reserves.

For the past six years, Egypt’s economy has suffered a persistent deficit in the current account as well as a dried-up foreign capital. First, this led the government to draw down on its foreign reserves, but eventually, it resorted to accumulating foreign debt to shore up its finances.

Consumption on overdrive

A closer look at Egypt’s consumption and growth patterns from 2011 to 2016 can help show why the economy has had to sustain a deficit of a significant enough size where both reserves were halved — relative to their peak at the end of 2010 — and external debt doubled.

On the one hand, economic growth has barely been able to counter the successive domestic and external shocks, which weakened income growth. On the other, the budget deficit has persistently been in double digits and one of the highest globally relative to GDP.

Of total budget spending, only 8.1 percent on average was directed to public infrastructure, while the rest was mostly spent on wages, subsidies and debt servicing. Expansionary fiscal policy has also triggered private spending by providing purchasing power to other sectors in the economy. Coupled with a fixed and overvalued exchange rate, this dynamic gave even more purchasing power to economic agents, thereby encouraging higher levels of consumption.

On average, during the same period, consumption in real terms grew by 4.4 percent so that even with anemic growth in investment, the economy still had to rely on foreign savings to meet its consumption and investment needs.

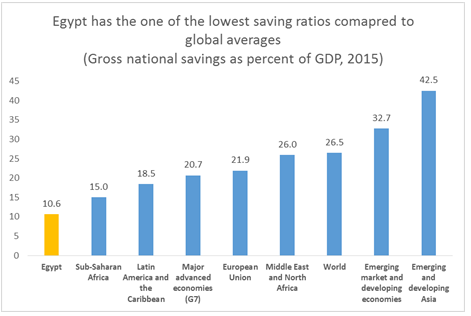

The high deficit, therefore, was mostly driven by overconsumption triggered by flawed policy signals. To put this in perspective, this following graph shows that Egypt has among the lowest saving ratios globally.

(Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, April 2017)

It is worth nothing that the main economic issue has not necessarily been overspending; rather it has been the composition of spending that likely perpetuated the deficit.

From an external sector perspective, both consumption and capital spending put pressure on the current account in the short term. However, their long-term effect is fundamentally different. The latter, if properly planned and managed, has the virtue of enhancing the future capacity of production and growth. Even if it is financed by borrowing, it could mean less pressure on the current account a few years down the line as well as a better ability to service debt.

In the past few years, however, due to uncertainty and a host of structural and regional factors, investment growth was lackluster. Little of the deficit that the economy financed from foreign debt, or by drawing from reserves, went to enhancing production capacity. Over time, it became more difficult to contain the deficit because underinvestment directly impacted economic growth and output.

Between debt and reform

With the closure and implementation of the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) program, the Egyptian economy is expected to once again show some much needed economic discipline. By restraining unduly high growth in public sector spending and liberalizing the exchange rate regime, the program will likely improve the performance of the current account in the short term. We have already seen some of this through the performance of the balance of payments over the last two quarters of the last fiscal year.

Nevertheless, ensuring long-term sustainability of debt will take deeper and far-reaching reforms, especially on the supply side of the economy.

Going forward, the economy’s thirst for capital is probably going to weigh on the current account, which will require a shrewd economic policy that boosts growth while containing the share of consumption. A growth model of this kind would primarily rely on enhancing competitiveness, productivity and capital accumulation, rather than fiscal or monetary stimulus. The latter will entail more debt and weaker capacity to service it. The former will not only improve growth dynamics, but will also help attract foreign direct investment to finance the ensuing current account deficit.

To help support recovery and sustainability of debt, the roles of monetary and fiscal policies will be central. Global currency movements and inflation differentials with trade partners means that a flexible exchange rate is necessary to maintain competitiveness. Avoiding significant misalignment in the value of the currency will also help keep domestic demand in check. Fiscal policy will have to stick firm to its consolidation path. It should expand the capital budget, while carefully prioritizing and managing public investments.

The sudden fever in Egypt’s external debt is a culmination of previous policy choices, and similarly, the future path will only be as sustainable as today’s policies.