In August 2016, Egypt signed an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to acquire a $12 billion loan, carrying with it a number of required reforms, setting the stage for the floatation of the Egyptian pound (EGP) in November of that year, after decades of following a fixed exchange rate policy by pegging the EGP to the United States dollar (USD).

On the November 2, 2016, just a day before the country’s currency was floated to allow it to be freely traded on the market, the USD was worth EGP 8.88 on the official exchange rate. The EGP’s value nearly halved overnight on the official exchange rate, becoming worth EGP 13.7 to the USD on the 4th of November. Its slide continued for the remainder of 2016, reaching EGP 19.66. Between early 2017 and early 2019, the EGP’s value remained stable, averaging between EGP 17 to EGP 18. Since then the pound has been gradually going up in value, reaching EGP 15.82 in January 2020.

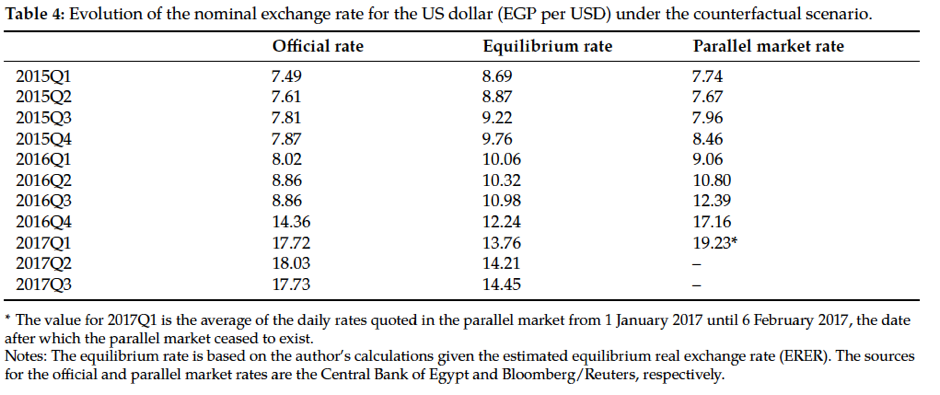

However, according to research conducted in 2018, the EGP was significantly undervalued after being floated and remained so until at least the third quarter of 2017. In his research paper titled “Much Ado about the Egyptian Pound: Exchange Rate Misalignment and the Path Towards Equilibrium,” Diaa Noureldin, assistant professor of economics at the American University in Cairo (AUC), found that the EGP was undervalued by 22% in the first quarter of 2017 when the official rate was on average EGP 17.72. According to Noureldin’s calculations, the actual rate should have been closer to EGP 13.76.

How does that work?

Official rates are more or less consistent with what is called the nominal effective exchange rate (NEER), which indicates how much of a domestic currency is needed to buy a foreign currency. However, it is an unadjusted weighted average. According to Investopedia, “NEER is not determined for each currency separately. Instead, one individual number, typically an index, expresses how a domestic currency’s value compares against multiple foreign currencies at once.”

Only the relative value of a currency is shown by the NEER, which does not reveal it in real terms. It does not account for price changes and inflation between different countries and trading partners. For that, there is the real effective exchange rate (REER), which the paper says is a “long-established measure of external competitiveness.”

Most important to Noureldin’s research was a third rate known as the equilibrium real exchange rate (ERER), which accounts for developments in what are called the “economic fundamentals” of the local economy. The paper stipulates that it is the version of the “real exchange rate value that simultaneously achieves internal and external balance.”

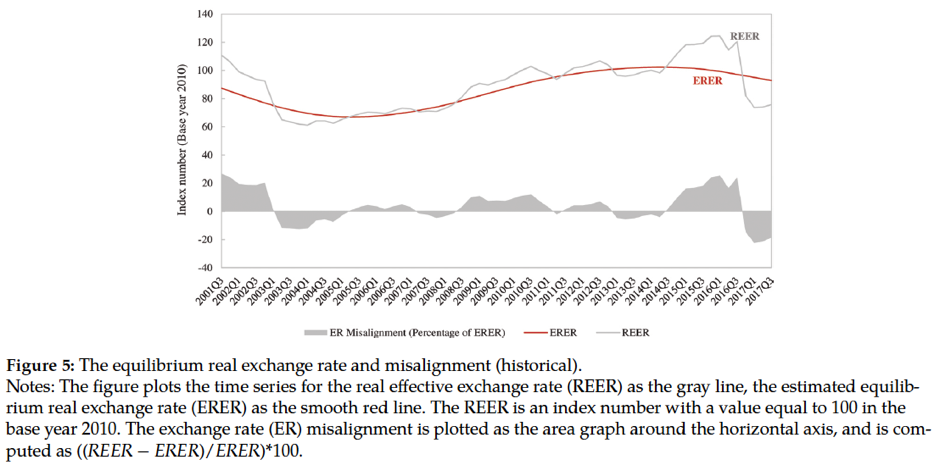

The economic fundamentals are productivity differential, government consumption, investment, terms of trade, net foreign assets and trade openness. Any fluctuations in any number of these fundamentals will affect a country’s ERER. When there is a discrepancy between the REER and the ERER, this is when a currency misalignment occurs, causing it to be undervalued or overvalued. These discrepancies “may arise due to an economic shock with a significantly destabilizing effect, frictions in the foreign exchange market that prohibit efficient price discovery, or a policy intervention such as supporting a currency peg.”

The Egyptian pound: from overvaluation to undervaluation

According to Noureldin’s paper, the EGP was overvalued by 24% in real terms just before it was floated, losing 32% of its value and becoming undervalued by almost 15% by the end of 2016. The overvaluation was due to a number of reasons, one of which was the fixed-rate currency pegging regime causing a significant misalignment between the REER and ERER.

Compounding this misalignment were the significant fluctuations in Egypt’s economic fundamentals during the highly turbulent period of 2011-2013 and continuing economic crises into 2016, when the the Egyptian pound was being kept artificially up on the exchange rate.

Significant overvaluation began at the start of 2015, when the country’s REER was going well above its ERER. The REER was going up thanks to the USD appreciating in value “against the currencies of Egypt’s other trade partners, and the increase in Egypt’s inflation,” which soared to double-digit figures in 2016 before the floatation. ERER was going down during this period due to declines in a number of economic fundamentals.

The undervaluation was caused by the exchange rate overshooting which in itself was a result of the previous currency controls. Another contributing factor was the constant anticipation throughout 2016 that the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) was going to float the pound, a decision that kept getting delayed. Anxieties over how much a devaluation was going to shoot up inflation, coupled with the CBE’s delays, caused high speculative demand for foreign currencies.

Noureldin states that this overshooting could have been avoided “had the exchange rate been determined more flexibly to reflect the changing economic fundamentals during this turbulent period.”