For decades, private developers have been building all sorts of real estate projects along Egypt’s Mediterranean coastline, from shopping malls to entertainment centers, and resorts to gated housing communities.

Starting in the 1970s, much of this development has been focused on lands lying to the west of Alexandria, with growth and expansion moving in a westward trajectory and exponentially increasing in the decades since.

With billboards all over Cairo and along the main highway of Egypt’s Mediterranean coast advertising projects both newly finished and currently under construction, in addition to megaprojects such as New Alamein City, the trend is showing no signs of slowing down.

These projects, on top of being investment ventures in and of themselves, arguably provide many attractive investment opportunities, including new spaces for offices and businesses, venues for events, and hotels for tourism.

What the North Coast (the Sahel el Shamaly as it is known colloquially) is perhaps most famous for is its luxury beach-side residential properties situated within high-walled gated communities. Affluent Egyptians buy up these properties for purposes of status and to have a house to get away to for the hot summer months. Perhaps most importantly, they are bought for the purpose of locking their wealth into an immovable asset that may appreciate in value over time.

However, in order for any particular investment to be made, its climate must seem attractive (meaning it must promise a profitable return over a given period of time) in order for said investment to be made in the first place.

But according to the latest data on projected rising sea levels in the Mediterranean, the actual climate (of the environmental variety) does not look like it is going to make for an attractive investment “climate” for Egypt’s North Coast real estate sector.

Reports as far back as 2008 predicted that Egypt was one of the most vulnerable countries to global climate change, and especially climate change-induced rising sea levels. The Nile Delta and Alexandria have for years now been on the front lines in the battle against the Mediterranean Sea’s rising waters.

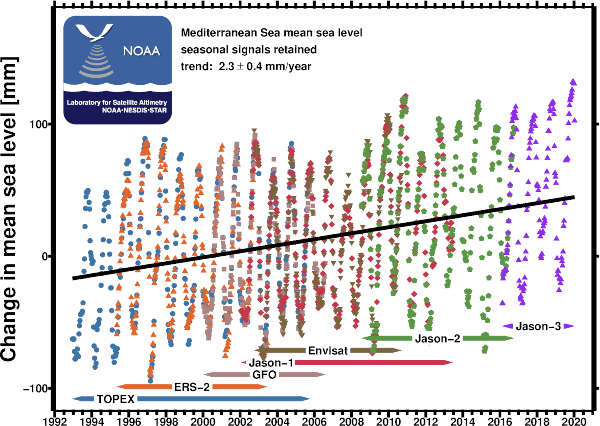

According to the latest data from the Laboratory for Satellite Altimetry (LSA), which collects its information on estimated sea level rises around the world from measurements provided by multiple satellite radar altimeters, the Mediterranean Sea’s mean sea levels have been rising between 0.4 to 2.3 millimeters per year since 1992.

A study based on 25 years of data collected from the United States-based National Aeronautical Space Agency (NASA) and European satellites released two years ago concluded that global sea levels are not rising at steady rates but are in fact accelerating over time. At these accelerated rates, average global sea level rises will reach 65 centimeters by 2100. The study’s lead author is Steve Nerem, a professor of Aerospace Engineering Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder, who is also a fellow at Colorado’s Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) and a member of NASA’s Sea Level Change Team. On the 2100 predicted estimates, he said: “[t]his is almost certainly a conservative estimate. […] Our extrapolation assumes that sea level continues to change in the future as it has over the last 25 years. Given the large changes we are seeing […] today, that’s not likely.”

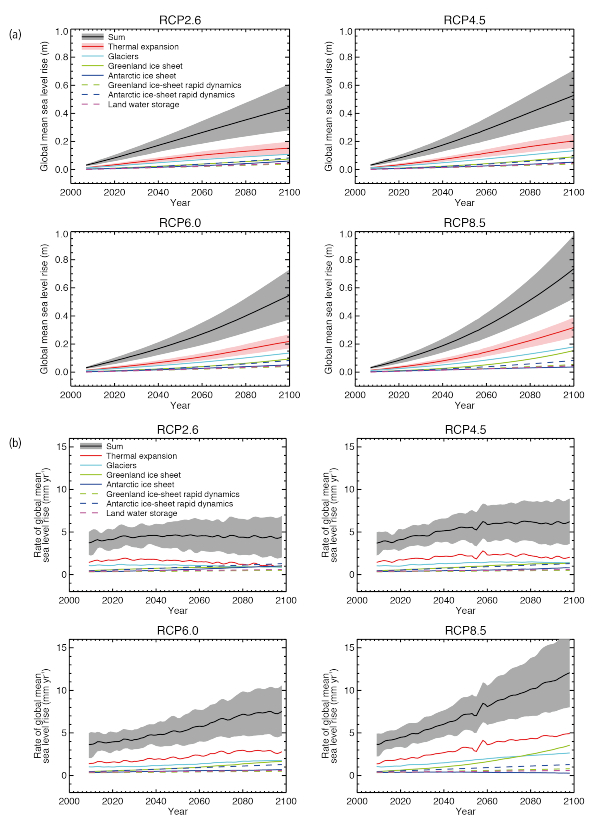

Detailed findings in a 2013 report by the United Nation’s (UN) main body for assessing the science behind climate change, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), showed that ice in both the north and south poles is set to continue melting at rates faster than they can regenerate for the rest of the century, contributing to global rising sea levels under several scenarios of varying intensities. “Over the course of this century, […] sources of mass loss appear set to exceed sources of mass gain, so that a continuing positive contribution to global sea level can be expected,” the report says. All the projections, including the best-case scenarios, are predicting dramatic increases. An updated IPCC report from 2019 reconfirmed these findings and predictions.

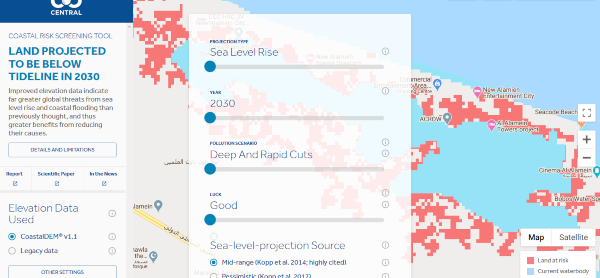

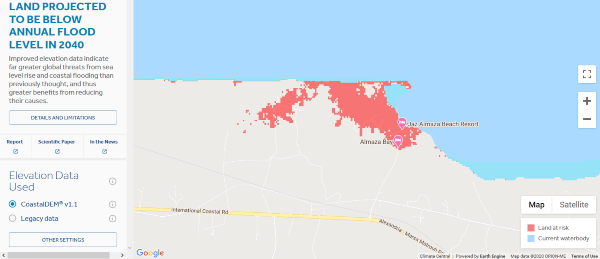

Last year, Climate Central, a US-based independent organization that conducts some of the world’s leading scientific research on climate change, published an interactive tool called CoastalDEM. The tool visually shows projected risks to coasts around the world based on the latest data regarding future rising sea levels. Settings can be changed to select a year, projected cuts to pollution, level of luck and whether to include average levels of annual flooding in the visual data.

The above screenshot is a 2030 projection of the area where New Alamein City is currently being built, based on the best-case scenario, however. Settings were at sea level rise exclusively, with good luck, and pollution levels set to “deep and rapid cuts.” Red areas indicate land that is at risk of going underwater.

However, according to Egypt Business Directory, in the last four years, there have been more than 70 oil and gas exploration agreements signed in Egypt, exceeding $6 billion in value. In February 2020 alone, five new agreements were signed with fossil fuel giants British Petroleum (BP), Royal Dutch Shell, Exxon Mobil, Chevron and Total.

Additionally, the annual Egypt Petroleum Show (EGYPS) was launched in 2017 and is one of the biggest oil and gas conferences in the North Africa and Mediterranean region. Evidently, it does not seem that the country is going to divest from carbon-emitting fossil fuel projects and transition towards carbon-neutrality anytime soon.

Assuming if Egypt even does become a carbon-neutral or carbon-negative economy within the coming decade, climate change is a global phenomenon and requires global efforts to be tackled. The country will still be at the mercy of spillover effects from around the world. According to a Guardian investigation released late last year, 50 of the world’s biggest oil companies are set to increase production to 7 million barrels per day by 2030. The UN’s Emissions Gap Report from 2019 says that greenhouse gas emissions have been rising 1.5% every year on average for the last decade.

This has been in spite of many international efforts to address climate change and to get governments and corporations to reduce their carbon footprint such as the Paris Climate Change Agreement that was signed by 196 states in 2016. Since then, the world’s largest investment banks and financial institutions pumped an estimated total of $1.9 trillion into the fossil fuel industry.

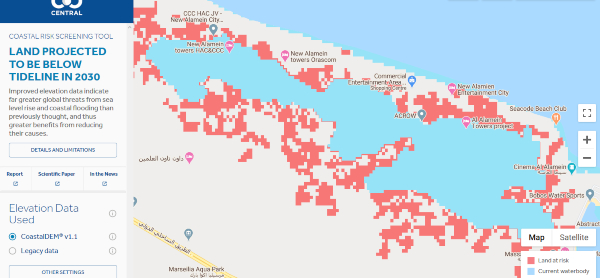

Changing the settings of the CoastalDEM tool to including average levels of annual flooding along with sea level rises, moderate cuts to pollution and medium luck, the 2030 projections for the same area look considerably worse.

The below screenshots are projections for the year 2040 of other North Coast destinations such as Marassi and Almaza Bay.

So how safe are investments and real estate along Egypt’s North Coast? Plenty of research and expert opinion is around to suggest you should start worrying about those villas and chalets in Sahel. The IPCC’s 2014 report of climate change impacts on urban areas specifically pointed to the significant risks to coastal properties, stating that “asset exposure is expected to increase more than 10-fold” by the 2070s with a 0.5 meter rise in sea levels.

Properties and other real estate developments on Egypt’s North Coast will certainly not be immune to these projections. At the 35th Cairo Climate Talks held in November 2015, Lima El-Hatow, who has done much research on how climate change will affect Egypt, as well as co-founding the Water Institute for the Nile, revealed that if a 50 centimeter rise in sea levels occurs in the next 50 to 60 years, there will be “severe damage” to the “large investments in summer resorts along the North West Coast of Egypt,” as well as “economic losses estimated at over $35 billion.”

For prospective buyers of Sahel properties close to the beach, it is probably not a wise investment unless aware of the risks involved. Speaking to Business Forward, Christopher Schroeder, an American entrepreneur, advisor and investor, says that “there is no doubt when one invests in properties, they take into consideration all the possible scenarios that could affect value. If one buys on the coast anywhere, they are thinking about odds of hurricane, flooding, access to resources in a problem and deciding if they want to take the risk and that the reward is worth that risk.”

Bearing that in mind, he still maintains that buying coastal properties that are highly vulnerable to the environment can be highly problematic, especially within the context of climate change. “Investing in property with well-known weather patterns still has significant risk. I see this with folks who have bought property here on the North Carolina coast and go years without a problem and then one event happens that can be costly or worse,” he says. “Weather is still hard to predict in the short, let alone longer term. In this environment of climate change, this uncertainty will only get more complex.”

Angus Blair, professor of practice at the business school of the American University in Cairo (AUC) and former chief operations officer at Egypt-based investment bank, Pharos Holding, told Business Forward that investment in low-lying coastal areas vulnerable to flooding and projected environmental changes would not be the best use of capital. Due to the accelerating rates of rising sea levels and global temperature records being broken every passing year, Blair says the “forecast that we had even a year ago may be out of date.”

“I have already advised some family that had larger houses on lower level land in the UK […] that they should sell up and move somewhere else because of what is going to happen within the next decade or 20 years,” he says. “Individuals have to become more awake to the [environmental] threats to their capital and have a more efficient use of their capital and invest somewhere that is going to be more sustainable for the longer term […] If they want to leave an asset to their children or grandchildren, they should really think seriously about whether it is a decent investment.”

Along with rising temperatures and sea levels, climate change is also set to increase the frequency of extreme weather events such as storms and flooding, turning what used to be rare phenomena into regular occurrences. Egypt’s North Coast resorts and gated compounds are empty throughout the winter season due to the cold and stormy weather. Such storms are only set to become stronger in intensity in the coming years and decades.

Blair cites parts of the UK that are frequently damaged by flooding. “Most housing in those areas are uninsurable now,” he says. Rebuilding damaged properties and building new projects in such areas does not make any sense, according to Blair, “because frankly, it is a massive waste of capital.”

“Certainly for grandchildren, it is not a good investment,” Abeer Elshennawy told Business Forward, an associate professor of economics at AUC, whose research interests specialize in environmental economics. “People already are feeling the [effects of] rising sea levels,” she says, citing a story of an acquaintance of hers who tried to get their North Coast property insured against climate-related damage. “The insurance company refused.” She laments the lack of public information and awareness of climate-related threats to assets, which is why many are still building and buying in the North Coast.

In another IPCC report published in 2014 on climate change’s economic impacts, specifically on insurance and financial services, it says: “climate change, including changed weather variability, is anticipated to increase losses and loss variability in various regions through more frequent and/or intensive weather disasters. This will challenge insurance systems to offer coverage for premiums that are still affordable, while at the same time requiring more risk-based capital. Adequate insurance coverage will be challenging in low- and middle-income countries. Other financial service activities can be affected depending on the exposure of invested assets/loan portfolios to climate change. This exposure includes not only physical damage but also regulatory/reputational effects, liability, and litigation risks.”

Ahmed El-Dorghamy, an energy and environment consultant at the sustainable growth division of the Center for Environment and Development for the Arab Region and Europe (CEDARE), says that minimal efforts have been taken to mitigate the risks of the Mediterranean’s rising seas. He says that developers have just been retreating properties that are particularly close to the beach and elevating their construction plans by half a meter. “They mitigate this risk by having their construction elevated. […] They say ‘these environmental folk say the sea is going to rise by half a meter in 20 or 50 years so let’s just elevate by half a meter and that is it,’” he tells Business Forward. He maintains that these measures do not go anywhere near enough and are in the absence of any serious mitigation efforts or contingency plans.

El-Dorghamy, who holds a Master’s degree in science and environmental engineering from the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden, and a PhD in sustainable development and behavioral sciences from the Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany, bemoans what he believes is a “short-term culture” in Egypt. He claims that from a practical point of view, North Coast developments are simply “wrong […] The planning of investments should be long-term.”

The headline of this article was changed on June 18, 2020 from “In the age of climate change-induced rising sea levels, are Egypt’s North Coast properties a wise investment?” to its current form. The main image was also changed from a rights owned one which depicted the construction of New Alamein City to the current one which is a generic drone image of a beach that is copyright free.