Business Forward’s “Sector Spotlight” series is a collaboration with the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies (ECES), presenting sector-specific insights based on ECES’s series “Views On The Crisis”: a sectoral analysis of how the COVID19 outbreak is affecting different parts of the Egyptian economy.

Part two of this series sheds light on one of the biggest and fastest growing industries in Egypt, food & beverage retail trade. Serving the largest consumer market in the region, Egypt’s food retail industry has been growing even in times of crises; how will the current crisis affect it and what is the way forward?

Key facts

Witnessing a booming growth rate that saw its volume of sales increase by over 161 times between 2009 and 2018, Egypt’s food & beverage retail trade is the second biggest retail sector in Egypt, coming second only to the automotive industry. With its size reaching $15 billion (EGP 242.5 billion) in 2018, it also employs over 1.4 million Egyptians as of 2016, and its sales volume has reached EGP 1383.3 billion, according to CAPMAS data – staggeringly up from EGP 8.6 billion in 2009.

Online grocery retail platforms, though still relatively small in size, have also witnessed growth over the past decade, making up 5.8% of total online retail trade in Egypt, and 0.08% of total trade in Egypt in 2018. The grocery retail sector is projected to grow at an average of 15-20% over the coming years, driven by the constant growth in the population.

In the first half of 2018, the total value of imported grocery products amounted to $1.8 billion (EGP 29 billion), with frozen meat and liver taking up a 36% share of total imports in the sector, followed by dairy and cheese at 10%, red tea and apples, each at 8%, and finally butter, fats, and oils at 7%. Egypt’s largest food & beverage trade partners are Brazil, USA, New Zealand, Kenya and India. But such imported products mostly make it to the shelves of certain types of retail outlets, which brings us to the next point.

Types of outlets

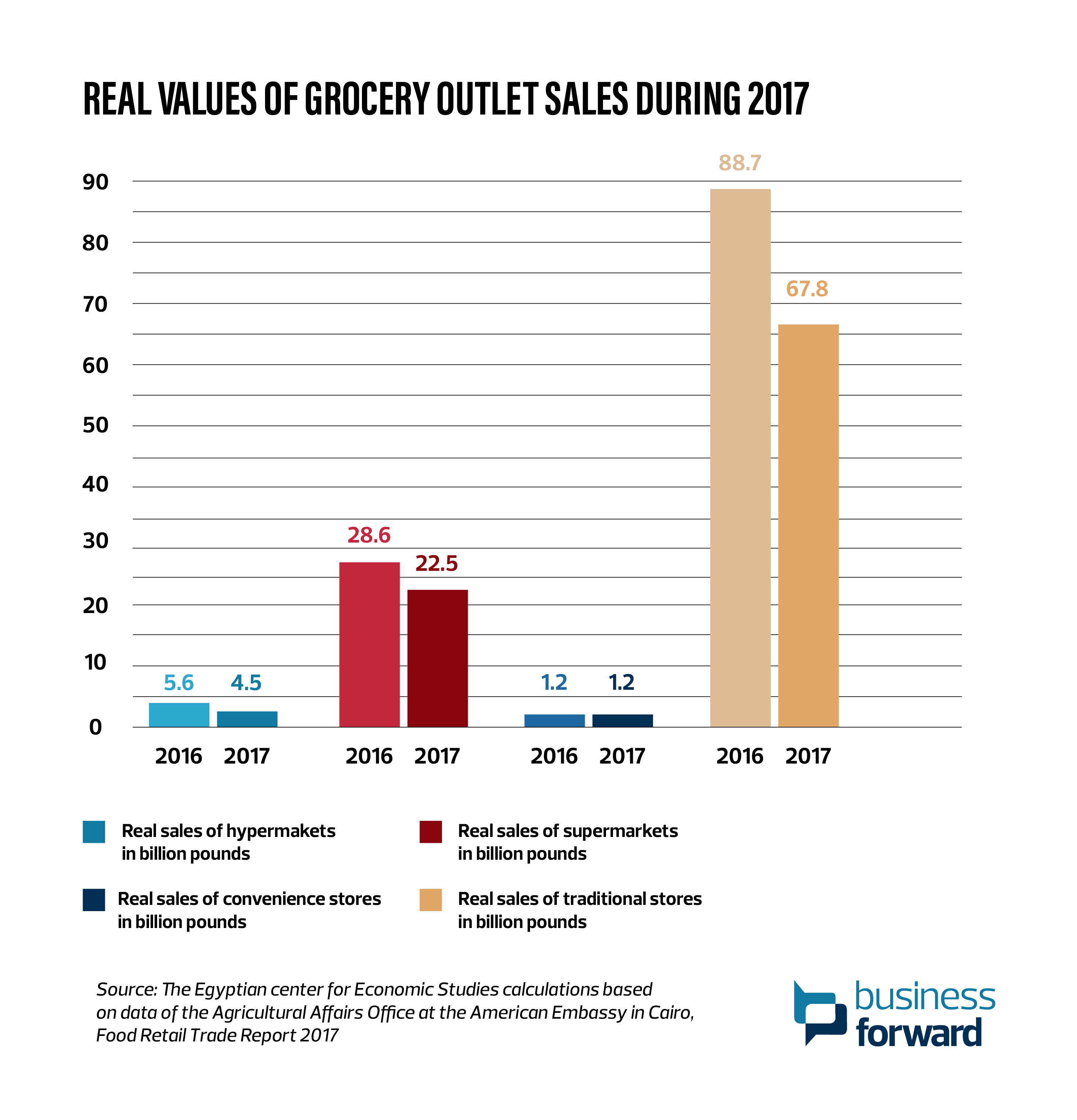

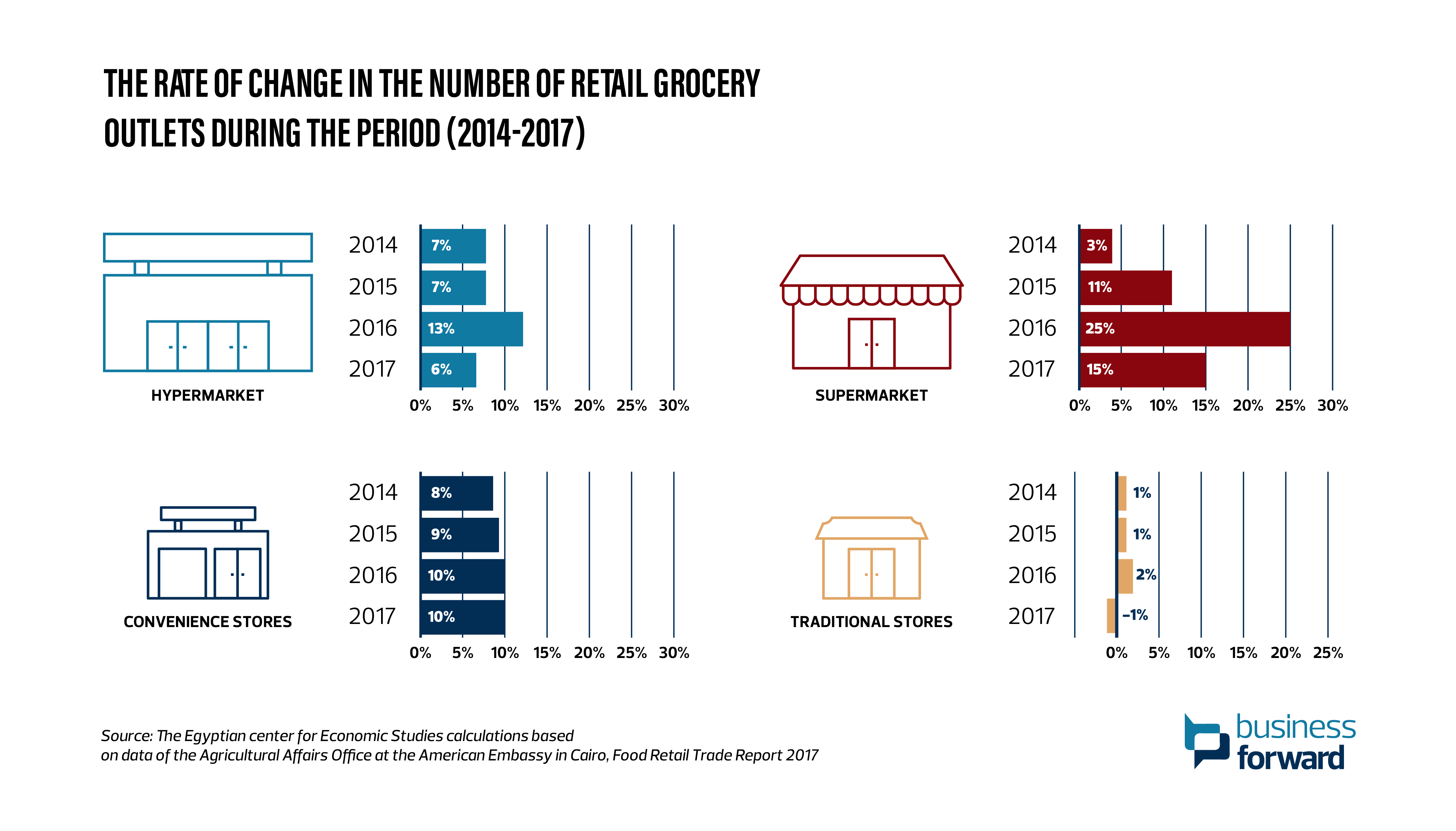

The grocery retail industry is broadly divided up into four main outlet types; traditional grocery stores; convenience stores (mostly at gas stations); supermarkets; and hypermarkets. With numbers of traditional grocery outlets amounting to over 115k (96.7% of total outlets), such outlets make up over 75% of grocery retail sales in 2017, with sales of each unit averaging at EGP 580k.

On the other end of the spectrum, there were only 37 hypermarkets in Egypt (0.03% of total outlets) as of 2017, with each unit having a sales value averaging at EGP 122.7 million, driven by the fact that such outlets cater mostly to high-income (hence high consumption) groups, compounded with selling highly priced imported products. Average sales per unit for supermarkets and convenience stores are at EGP 18.5 million and EGP 4.7 million, respectively.

Hypermarkets have high intensity of formal employment, with supermarkets and convenience stores having medium intensity of such employment. Traditional grocers, on the other hand, have mostly informal employment, which according to ECES amount to 30% of total informal employment in Egypt.

It is noted here that hypermarkets and big-chain supermarkets have a comparative advantage over traditional grocers, with their supply networks linked with what ECES describes as a ‘huge value chain’, enabling them to offer products at competitive prices. Linking traditional grocers to such value chains could help them achieve the same efficiency and competitiveness, especially given that they make up the vast majority of grocery retail outlets in Egypt, and subsequently serve customers from all socioeconomic classes, and across rural and urban areas – in contrast to hypermarkets which are often in remote urban locations that require commuting.

Further highlighting that imbalance between traditional grocers and the more high-end supermarkets and hypermarkets, Damyana Bakardzhieva, visiting associate professor at the AUC School of Business department of economics, says: “There might be more supermarkets opening up simply because there are newer and newer compounds and neighborhoods built around the country that need to be served, but if the overall sales are declining in real terms, I don’t think that we can call this true growth.”

“There surely is income disparity accounting for the growth in number of hypermarkets and supermarkets,” adds Bakardzhieva. “In many cases shopping there requires the use of a car, making them clearly not accessible to the lower-income households. There’s probably also a part of the phenomenon that could be attributed to changing consumer behavior and the “westernization” of consumer habits, but to a smaller extent, and even that trend would mostly affect the relatively affluent citizens while leaving behind those close to the poverty line.”

Patterns in previous crises

In the past decade, the Egyptian economy was subjected to two major crises that had varying effects on different sectors; namely the crisis following January 25 revolution in 2011, and the one following the liberalization of the EGP in late 2016, which decreased its value, and hence Egyptians’ purchasing power, by 50% against the US dollar.

The grocery retail trade in Egypt wasn’t shielded from the impact of these crises, albeit the effect was less severe than in other sectors. In 2011, sales across different outlets fell by 4% in comparison with 2010 – from EGP 152 billion to EGP 146 billion – a decline mostly driven by shortage of imported, high priced products, with traditional grocers seeing the steepest decline.

When it comes to hypermarkets, a 31% growth rate was reported in 2011, a trend which continued well into 2012 with a 12% growth rate, before declining by 3% in 2013. Similarly, supermarkets grew in 2011 and 2012 by 7% and 3%, respectively, before declining by 2% in 2013. Traditional grocers witnessed the biggest losses, shrinking by 6% in 2011, 2% in 2012 and a further 2% in 2013. Growth of convenience stores stagnated at zero in 2011, declined by 6% in 2012, before cutting its losses with a 3% hike in 2013.

The decline in the market share of traditional grocers should be tackled by enabling them to provide the same convenience offered by bigger retail outlets, like home deliveries as a start.

“Traditional grocery stores can retain their market share if they provide their customers with more convenience,” explains Bakardzhieva. “Deliveries with the possibility to order by phone could be the key to maintaining the activity in the sector and to creating even more jobs. Private and public investment could be channeled to providing a lease scheme for small delivery-equipped scooters or motorbikes and mobile phones, as well as to providing training on establishing trustworthy and courteous customer relationships. Longer/different opening hours and operating during weekends and holidays can also provide a niche for them.”

The aftermath of the liberalization of the EGP and the subsequent shortage of USD in the market was felt across the board in 2017, the year which witnessed the highest inflation rate in over a decade. In that year, sales of traditional grocers declined by 23%, convenience story by 4%, supermarkets by 21%, and hypermarkets by 19%.

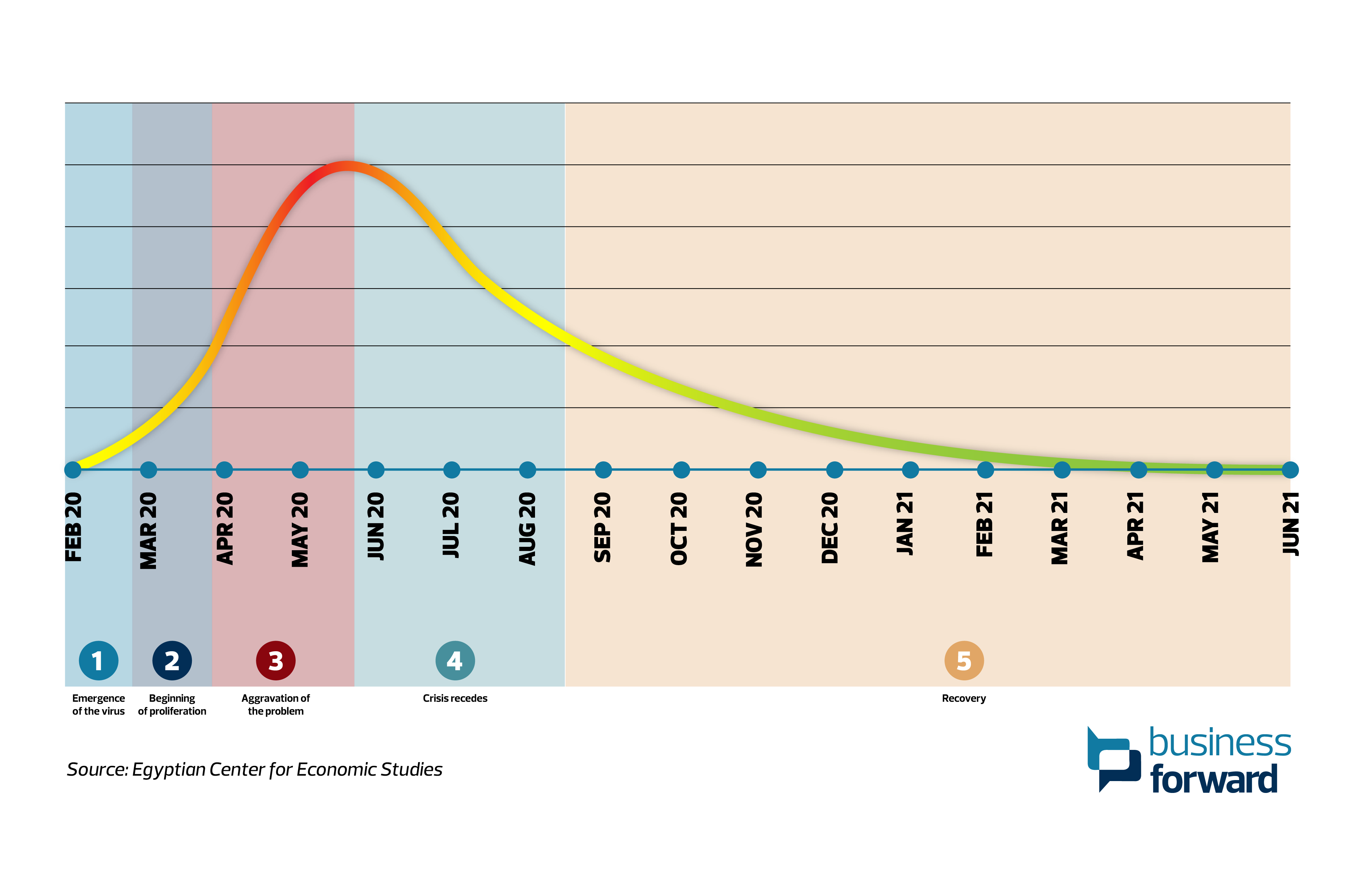

COVID-19 crisis

While the long-term impact of the current crisis on the sector could be challenging to predict, the onset of the pandemic had rippling effects on the industry since beginning of curfew measures in mid-March. An unprecedented boom in sales volume was recorded in hypermarkets and supermarkets in the first three weeks of lockdown measures, with the increase ranging between 40% and 100% per store, driven by hoarding of products on part of the consumers in anticipation of the impact of the crisis. That was met with an immediate hike in employment in these two outlet types, ranging from 20% and 40% – though mostly informal.

Also witnessing increased sales, traditional grocers weren’t as fortunate as hypermarkets and supermarkets, recording a sales growth between 20% and 40% in the same period. That could be due to several factors, according to ECES, like consumers preferring to buy from ‘safer outlets’ as well as traditional grocers’ weaker storage capacity. Additionally, the central bank’s decision to cap daily withdrawals from bank accounts has contributed to limiting the potential growth in sales for traditional grocers.

Sales amidst the pandemic

Sales amidst the pandemic

Similarly to hypermarkets, the online retail side of business also witnessed a positive effect in the wake of pandemic.

“I think COVID-19 will have a positive effect on online retail in general in Egypt,” said Omar El Etriby, founder of prominent grocery platform El-Mazr3a, to Business Forward. “More people will buy online for convenience and safety, not just in grocery, but across all industries. I also think the current crisis could cause more ordering efficiency with many businesses adopting the DM (direct message) for order model through their social media platforms.”

The initial boom didn’t, however, persist, with the fourth week – coinciding with the beginning of Ramadan – seeing sales grow by a figure between 20% and 60% only, lower than is usually the case with the advent of Ramadan. This rate continued well into mid-May for hypermarkets and supermarkets, with traditional stores returning to their normal sales levels in the same period.

Revealed industry weaknesses and potential solutions

In the process of creating the paper, ECES found that accurate database on retail outlets and their distribution doesn’t exist. Also the fact that most retail trade in Egypt is unorganized has been suggested by ECES as a barrier to the industry achieving higher efficiency, and quality of products and packaging methods.

The ECES paper highlighted a number of interventions that would help mitigate the impacts of COVID-19 on Egypt’s grocery retail sector, starting with the government practicing “strict control over all outlets to counter any monopolistic practices, or attempts to hide commodities, while adopting legislation related to health procedures.” It also calls upon strengthening of the e-commerce infrastructure in Egypt, a suggestion echoed by El-Etriby.

“I would love to see Egypt develop and implement a proper postcode system instead of the GPS and directions-based system we have now,” says El-Etriby. “That would actually mean the customer could order quickly we can deliver quicker with less physical communication.”

Furthermore, ECES suggests establishing a committee which has access to the status of inventory in each governorate across the country, which would help decision-makers direct surplus in certain areas to those who are experiencing shortages.

Bakardzhieva questions the feasibility of such a recommendation.

“I’m not sure how technically feasible such a policy is given the current communication infrastructure. Improving this infrastructure is surely essential to developing any retail sector in the country. Investing in anything that can facilitate ordering by phone or online and home or office deliveries would generate the most economic and social return.’

Access the full ECES study through here ?????? ?? ?????