As part of Business Forward’s 2019 anniversary event hosted by the AUC School of Business at AUC’s Tahrir campus on December 2, Dr Laila Iskandar, the founder of CID Consulting, addressed in her talk the importance of ensuring social justice in the wake of Egypt’s conclusion of the IMF-sponsoed economic reform program.

Iskandar was formerly the minister of environmental affairs, after which she became the minister of state for urban renewal and informal settlements. Iskandar didn’t give the usual talk about social justice with regards to social welfare and protection for the poorest and most vulnerable. Instead, she decided to speak from a business perspective and talk about the business activity within the country’s base of the pyramid.

“I would like to present to you a different view. It’s about business, right? So I’m going to talk about the business community of Egypt who are at the bottom of the pyramid,” she said.

According to Iskandar, the debate about social justice should not be about poverty but should rather be about levels of inequality. “Is it about lifting the poor out of poverty? Is it about the base of the pyramid? Is it about value chain? I think when we talk about base of the pyramid, trickle down, social protection, we are actually deflecting from the real issue and the real issue is inequality.”

The focus of her talk was on Egypt’s huge informal sector, the widely accepted assumptions about it, the myths, the benefits the sector brings to Egyptians and the economy, and how it can be further utilized to contribute even more to the Egyptian economy.

There has been a lot of talk in Egypt in recent years, and even some efforts, to reign in the informal sector in order to formalize its economic activities and finances. This drive has been motivated by a desire to ensure that informal enterprises are taxed accordingly to boost the country’s tax revenues.

One thing to note is that the informal sector is big, very big, and reflects worldwide trends. Globally, there are 2 billion people working informally, accounting for around 61% of the world’s working population. In Egypt’s case, 94% of those without any formal education work in the informal sector. 52% of those with secondary education and 24% of those with tertiary education also work in the informal sector. So a substantial proportion of Egypt’s population with highly varying degrees of skills and education are informally employed.

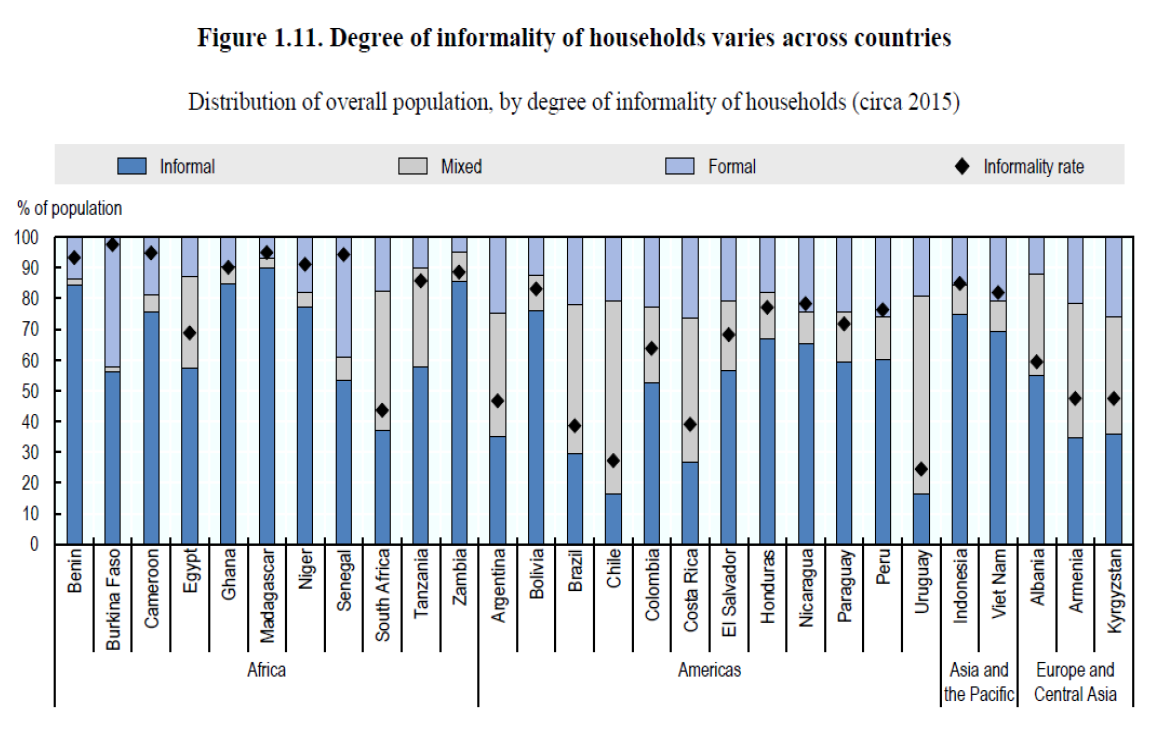

In 2015, almost 60% of households were in informality, where all the working members of the household were employed in the informal sector. Almost 30% of households were home to a mix of people working in both the formal and informal sectors, leaving only 10% of households with all their members in formal employment.

One of the most common misconceptions about the informal sector in Egypt is that it doesn’t pay taxes and doesn’t contribute to the state’s revenue. Iskandar explained that “we need to dispel a few myths. One of them is that all these people in the informal sector are rogues. They’re rascals. They’re men who are avoiding taxes. In fact, now, the narrative and the research on the informal market is about families. It’s not about a few people riding tok-toks and not paying taxes. It’s families.”

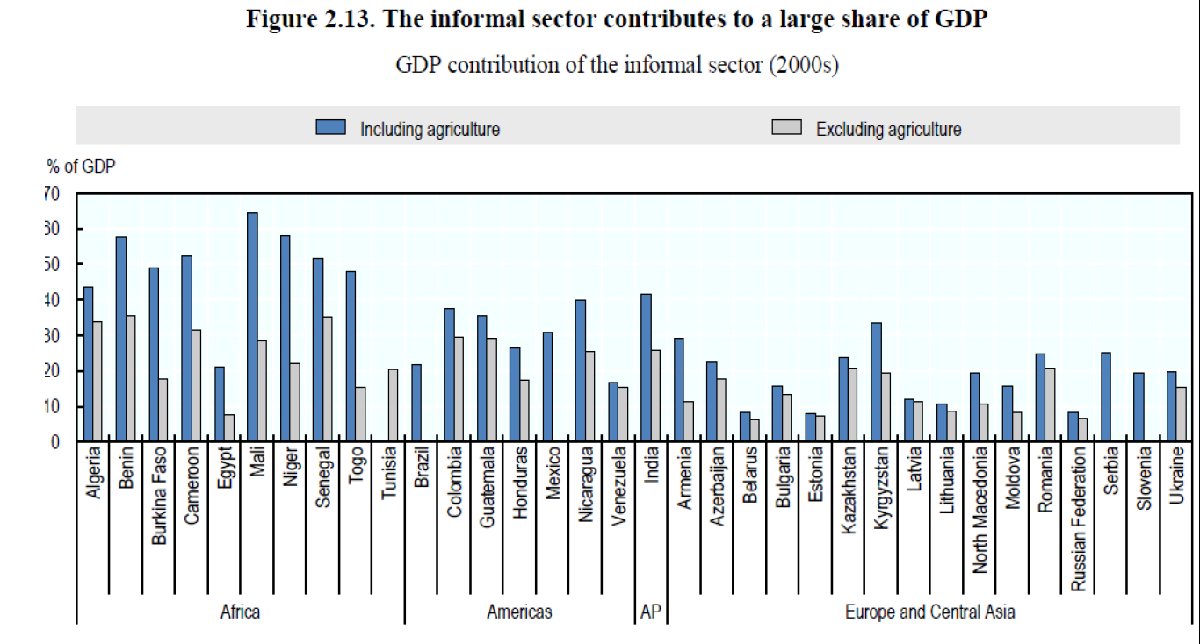

The perception of those employed in the informal sector as people who want to avoid taxes is not helpful and is in fact, inaccurate. Instead, those who work informally are impoverished families trying to survive. On the contrary, the informal sector does actually contribute significantly to overall economic output. It provides technical and vocational skills training required for the nature of work usually found in the sector, and provides services and products which contribute to the market and GDP growth. According to data from the 2000s, the informal sector (when including informal activities in the agricultural sector) accounted for around 20% of Egypt’s GDP.

With regards to taxation, “contrary to common belief, informal workers and firms contribute to tax collection efforts both directly, through indirect taxes and presumptive taxes, and indirectly, through the links between formal and informal outputs.”

Iskandar also dispelled the myth that formalising will boost the government’s tax revenue. In fact, because informal businesses are mostly low-income, their formal tax contributions will be negligible, and a poorly designed taxation regime may even causes these businesses to fail, depleting the country of employment, income, and productivity.

Instead, Iskandar emphasised the need to upgrade the businesses and skills of workers in the informal sector before any formalisation takes place. “Beyond registration, you need to make sure that they get the specific skills that you need to integrate and then talk about formalising them and registering them.”

Through CID Consulting, Iskandar herself helped to register over 100 small waste collection companies. “But do you think they have any contracts with the municipality?” she asked rhetorically. “None.”

It’s not enough to merely become registered and formalised. Ease of doing business in the formal sector needs to improve in order for informal enterprises coming into the sector to survive, succeed, and continue positively contributing to the Egyptian economy.