With the help of small amounts of funding and training, hundreds of young women in the Upper Egyptian governorate of Minya were able to heave themselves out of unemployment through their own micro businesses, according to findings by the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL).

In 2016, a local NGO known as Maan (or Together Association for Development and Environment in English), carried out an employment scheme in the governorate of Minya to help around 1000 youth living in poverty and unemployment.

Assessing and evaluating the scheme was J-PAL, a research center based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) that conducts rigorous research into poverty reduction programs to create strong scientific evidence to inform policymaking.

The Minya scheme was only one of several funded by the Emergency Employment Investment Project (EEPI), an initiative funded by the European Union (EU) that began in 2014. The World Bank administered the fund in coordination with the Egyptian government.

One of the objectives of this funding was to tackle chronic issues of youth unemployment in Egypt by providing emergency employment programs, according to Rahma Ali, senior research associate at J-PAL’s Middle East and North Africa (MENA) office.

Deciding which local organizations to fund was the Social Fund for Development (SFD), one of the Egyptian government’s development arms, which later reformed to become the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise Development Agency (MSMEDA).

MSMEDA managed a selection process of local non-government organizations (NGOs) and community development associations (CDAs) to access this funding for implementing their own proposed intervention schemes to boost employment in their local areas.

“This is a smart move because oftentimes, the people who work and live in a community will understand what the community needs a lot more than some bureaucrat from the World Bank who hasn’t spent anytime there. Lots of different CDAs applied for the funding and they also wanted to evaluate the impact of their programs,” says Adam Osman, co-scientific director at J-PAL MENA.

Ali adds: “These local NGOs and local entities would be the main implementers who would design the program and provide the training services and all the services that lead to the goal of promoting youth employment.”

All the different organizations had different ideas for creating jobs but there was no evidence to prove which scheme would be the most effective or even effective at all.

Osman adds that “the World Bank and the SFD had the foresight to use this as an opportunity to try to learn what works and what works best.”

Maan were one of the approved recipients of the fund for their idea in Minya. “The main objective of the interventions in Minya was to help these youth to start their own businesses as part of a self-employment intervention,” says Ali.

Their scheme involved several interventions which included seed funding, vocational and financial training, and counseling.

Seed funding (or capital assistance) was provided in two forms: one was an in-kind grant in the form of equipment which would help the participants start their own business, such as livestock and sewing machines; and the other was a cash loan.

Vocational training included hands-on training on a specific skill such as livestock breeding and sewing. Financial training mainly included how to start a business, how to calculate revenues and profits and how to expand their projects.

“The counseling in the self-employment context took the form of one-to-one sessions where the counselor was an expert in the skill that the participant selected,” Ali explains. “For example, if the participant selected livestock breeding, then we have an expert who is aware of animal health and how to manage a livestock business. The counseling sessions help the participants on how to grow their business.”

J-PAL conduct research on poverty programs by conducting randomized control trials, similar to studies that are undertaken in the medical field where some patients take a certain drug and others are given a placebo and another group may not be given anything at all.

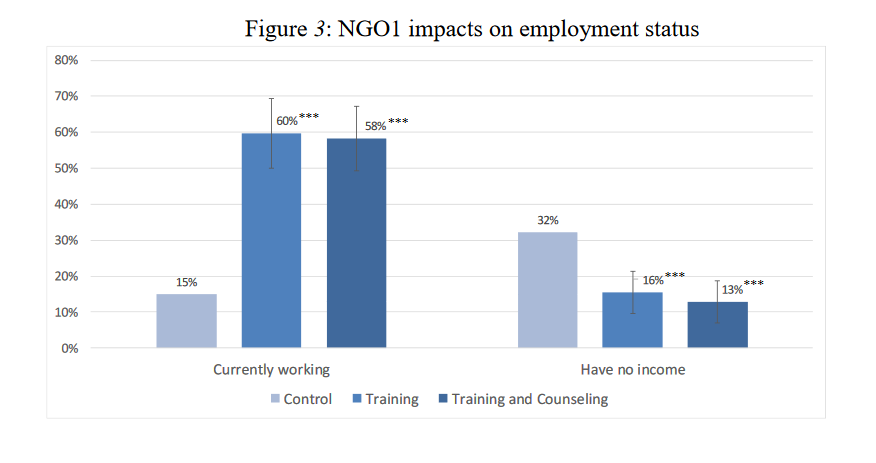

As with J-PAL’s other impact evaluations around the world, the participants in the program were split into one control group and two treatment groups. The control group did not receive any help or intervention. One treatment group received vocational and financial training and seed funding. Another treatment group received all those interventions in addition to counseling.

“J-PAL’s role was to evaluate the program and assess its impacts on participants in terms of assessing labor market outcomes, employment and income,” Ali says.

There were exactly 1011 participants who were 80 percent women and 20 percent men, aged 18 to 35, with each sample group containing around 300 individuals.

On why there happened to be more women than men, Osman says “this was primarily driven by the fact that women were just more interested in these programs.”

Before the program started, J-PAL did a data collection round to see how the participants were doing to use as a baseline. Data was then collected approximately one year after the beginning of the program for a short-to-medium term impact evaluation.

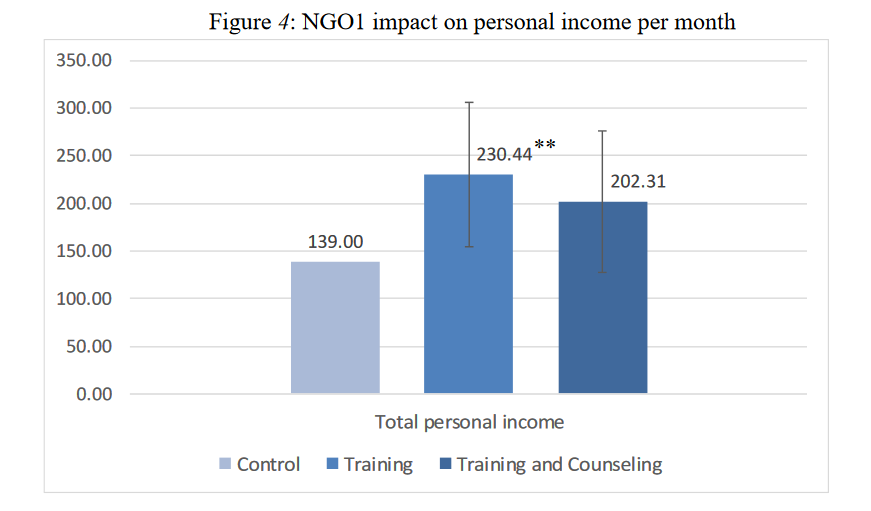

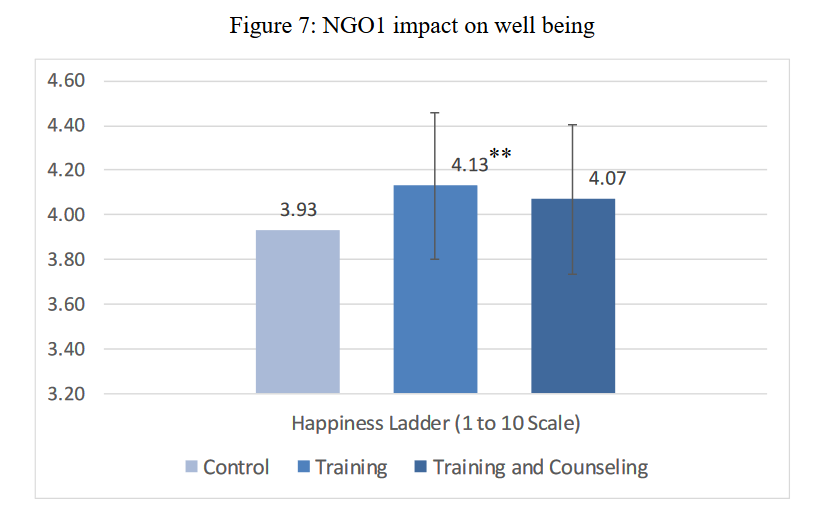

What they found was an amazing increase in employment in the treatment groups, with 60 percent reporting they were in employment. This was in stark contrast to the control group which only reported 15 percent in employment. There was also around a 58 percent increase in income. However, there did not seem to be much difference between the two treatment groups. Counseling seemed to have a statistically insignificant effect, according to Ali and Osman.

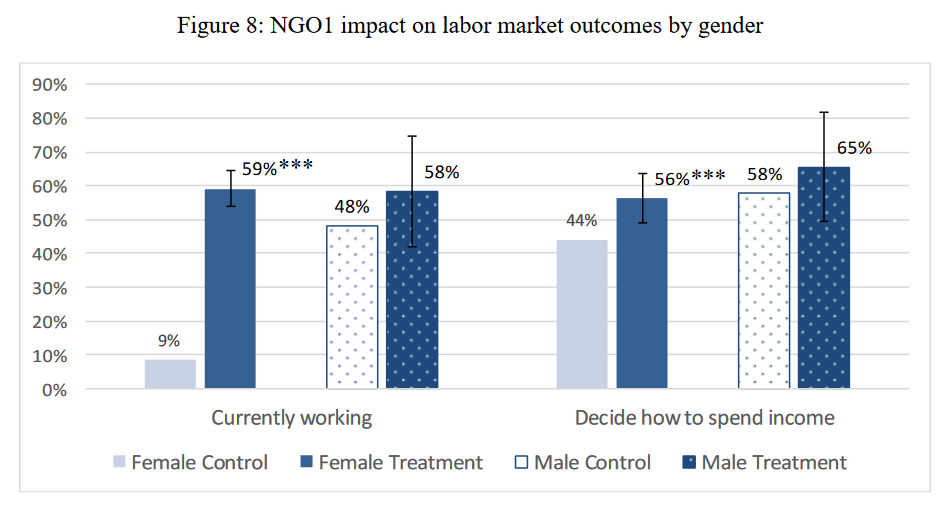

However, when the sample groups were broken down by gender, the findings showed even more dramatic numbers.

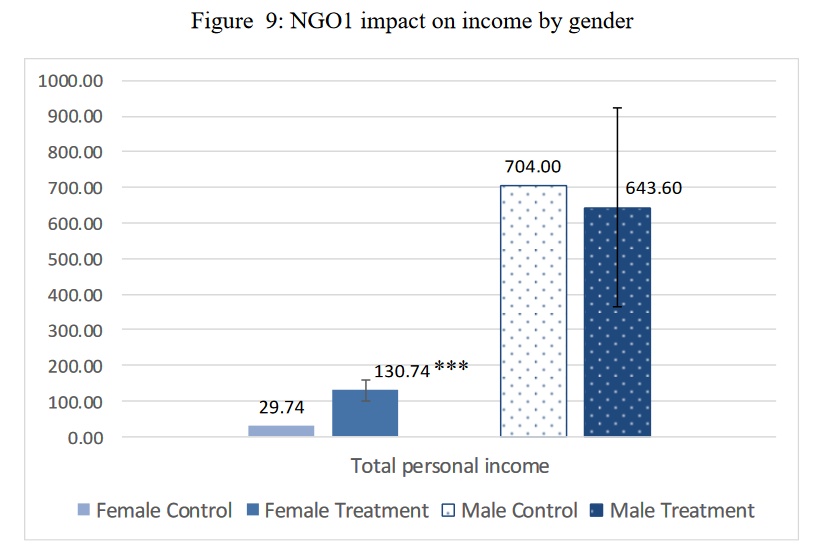

“What we found to be very interesting in the heterogeneity analysis was that the program impacts were significantly larger for females than males,” Ali says. “The main explanation for this was that females already start from a very poor baseline. The majority of females were not working or engaged in any income generating activities at the baseline. The impacts of the intervention in terms of the jump that we’ve seen in employed females were much more than we had expected considering the scope of the intervention.”

Among females only, 9 percent of those in the control group were working. On the other hand, 59 percent of the women in the treatment groups reported they were working.

“This difference of 50 percent is shocking. This may be the largest impact we’ve ever seen,” Osman exclaims.

Among men, only 10 percent more were working in the treatment groups.

The findings also showcased an important empowerment aspect. There was a 26 percent increase in the numbers of those who said they now decided how to spend their income. Since the majority of the participants were women, the evaluation said that this meant better labor market outcomes empower women financially and provided them with more freedom of choice.

Even when looking at income, women benefitted more from the interventions. The average monthly incomes of the females in the control group was EGP 29.74. As for the treatment groups, women saw an average monthly income of EGP 130.74. There seemed to be little change among male participants.

“In addition, there was also increases in total hours worked and asset ownership. In general, all the indicators that we’re getting is that there is an increase in participation in labor market activities. People are working more. They’re getting more income. They are identifying themselves as working individuals,” Ali says.

While participants in the treatment groups only reported small, perhaps insignificant increases in levels of happiness, they had much more optimistic outlooks on the future, feeling more hopeful about where they will be in a year’s time.

“The main important takeaway is that prior to this study, we had no rigorous experimental evidence about the effectiveness of employment programs in Egypt,” Osman says, emphasizing the significance of these findings.

He adds that another important takeaway is how this goes against the grain of already established research. “There’s a large international literature that says employment programs usually don’t work. Maybe it doesn’t work in other countries but let’s check and see if it works in Egypt and we found that it works quite well for women. This implies that women are facing a different set of constraints than men. Future research will try to understand what those constraints are and how can we help women overcome those constraints.”

When J-PAL come back to the Minya program later this year to conduct a four-year follow-up evaluation, they will be paying closer attention to how counseling may have affected the sample group over the long term, which is still being debated.

“Counseling, at least in the short term, doesn’t seem to be efficient. It’s possible that the counseling needs longer to actually show an effect. That’s why we’re excited about that,” Osman says.

“The four-year follow-up data will allow us to see two things: Did this intervention actually lead to any long-term impacts? A lot of times, we see short-term impacts that fade out over time. Does that happen here? And if so, we should keep that in mind for thinking about the cost effectiveness of this program. If you have a program that just helps somebody for a year, that’s different from a program that helps somebody for four years. When you’re trying to figure out if it is worth spending money on these things, you want to know how long the benefit will last for.”