Listen to the article

How does the world accelerate economic growth despite the modern era’s dual dimension constraints: social and environmental constraints? That is the million-dollar question economists have been trying to answer for decades. If humanity can live within the ‘doughnut’, it will find a way to encompass social foundations, environmental sustainability and economic growth to sustainably achieve the tripartite objectives of social, environmental and economic development.

In a recent webinar by the John D. Gerhart Center of the AUC School of Business, Kate Raworth, economist and professor at Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute, professor of practice at Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences and co-founder of Doughnut Economics Action Lab, highlights the concept of Doughnut Economics, bringing forward some fascinating insights.

Outdated economics of the 20th century

“When I was a student in the 1990s, I was frustrated by the economics I was taught, and I believe it’s out of date.”

“I’m sitting in one of the richest countries in the world, yet our politicians and economic advisers believe that the solution of the UK’s problems and all high-income countries too, is more growth, and I believe there is something profoundly wrong with that.”

Raworth further elaborated that these ideas of markets first, rational selfish humanity and endless growth of 20th century economics have underpinned the down-sloping situation the world currently finds itself in. “The 21st century has begun with multiple crises; a financial meltdown in 2008, climate and ecological breakdown now, and the COVID-19 lockdown we have all just endured and still endure.”

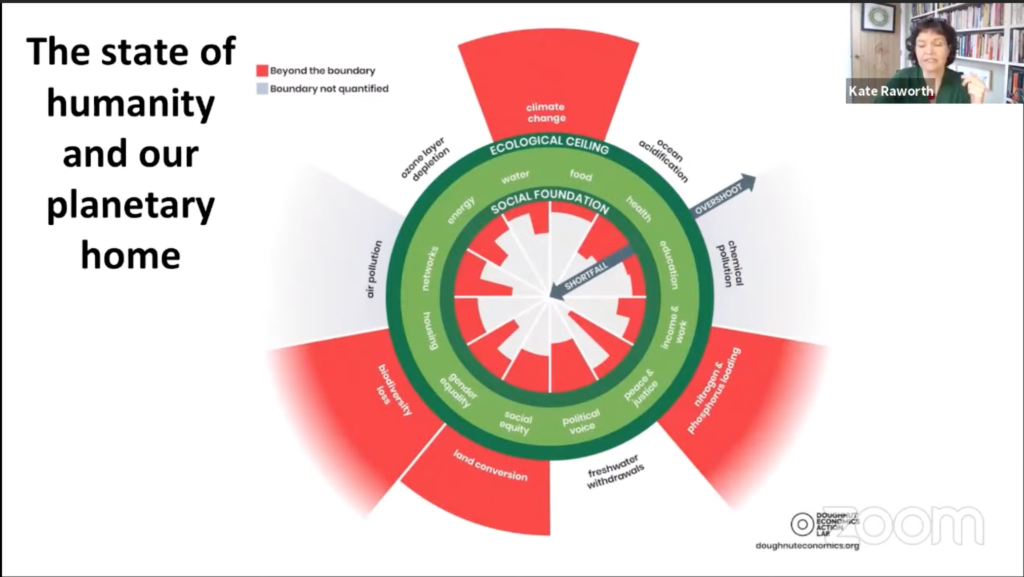

Screenshot from Gerhart Center webinar: “Can Humanity Live within the Doughnut?”, featuring Kate Raworth on April 7, 2021.

Following that line of thought, the crises emerge from the very systems that we have created based on outdated 20th century economic analyses that are inherently flawed. Raworth emphasizes that notion and says, “I believe all three crises despite being portrayed differently in the media, emerge from systems that depend upon endless expansion, that’s the only thing that the financial system, [the] energy and industrial system, and [the] human settlement system have in common.”

“We need to transform our vision away from the idea that progress is always everywhere; [that] endless expansion,” said Raworth.

Transformational thinking about growth and development

According to Raworth, the ‘doughnut’ approach is here to change how the world’s leading economists view social, environmental and economic growth. The idea behind doughnut economics is to leave nobody falling behind in the hole in the middle of the doughnut. That hole represents the situation where people do not have the resources they need for food, healthcare, housing, education, political voice, income, etc.

Screenshot from the Gerhart Center webinar: “Can Humanity Live within the Doughnut?”, featuring Kate Raworth on April 7, 2021.

However, the doughnut must maintain the perfect balance that sustains global equality. “[We must ensure that we] don’t overshoot the outer ring because that is where we use Earth’s resources so much and in such a way that we break down the life-supporting systems of this planet,” emphasizes Raworth.

The social foundation of the doughnut is represented through the twelve social dimensions of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which world governments are committed to. Whereas the outside ecological ceiling of the doughnut comes from planetary boundaries.

Screenshot from Gerhart Center webinar: “Can Humanity Live within the Doughnut?”, featuring Kate Raworth on April 7, 2021.

“So, in the simplest of ways, I say that the goal of the doughnut is to meet the needs of all people within the means of the living planet.”

“If this is the goal we want to get to, the trouble is we are very far, we need to come back into this space from both sides at the same time, and I believe this is our generational challenge.”

Raworth’s notion of outdated economics indicates that economic theorists, policymakers and business leaders of the previous centuries did not see this picture because this was not their challenge. They were not trying to solve this, so it would be strange to believe that their theories, policies and business designs would bring us to this realization.

“We need to recreate and reinvent economic thinking and practice for our own times and our own challenges,” according to Raworth.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a single country that has reached the goal of the doughnut. Low-income states have the challenge of meeting people’s needs for the first time without overshooting planetary boundaries in the way that every country before them has done. Middle-income states need to meet people’s needs fully for the first time while already coming back within planetary boundaries. Finally, high-income states must meet every person’s needs – which they can do since they have the income to afford it – but massively come back within planetary boundaries.

“There is no such thing as a developed country. There’s nothing developed about destroying the life-supporting systems of the planet. We are all developing countries in the sense that we are all on transformative journeys,” believes Raworth.

Turning it around

“The starting point has to shift from the usual supply and demand of economics to the big picture, recognizing that the economy is embedded in society and that society, in turn, is embedded in the living world.”

Furthermore, the concept of the doughnut must be downscaled from the global level to a local level since that is where actual policymaking takes place. “To get cities into the doughnut, we need to create two dynamics; we need them to become regenerative and distributive by design.”

To elaborate, regenerative economies are where resources aren’t used up; they’re used again and again, creating a circular economy. For instance, in Nairobi, waste from community-run toilets is collected daily and turned into fertilizer applied to agricultural fields, so the nutrient loop is gradually being closed. Furthermore, distributive economies in cities share opportunity and value with all who co-create it rather than concentrating it in the hands of a few.

Another equally important point is how the institutions of a city are designed. Rather than focusing on making cities grow, institutions must focus on making cities thrive.

“There are five design traits we can think through for how to make cities thrive; purpose, networks, governance, ownership and finance.”

“For a city to ensure all five design traits are in service of a thriving future, diverse local actors must promote this, including anchor institutions, NGOs, community-based organizations, mayor and city administration and business networks. If all cities follow that path, we will begin to see global transformation in the global doughnut through the transformation of city doughnuts.”

The full webinar recording can be accessed here.